Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction is a unique and very interstitial writing guide that uses original images and visual exercises to educate and inspire. The book won the 2014 British Science Fiction Association Award for Best Non-Fiction, and is a Hugo Award finalist for Best Related Work. I talked to editor Jeff VanderMeer and artist Jeremy Zerfoss about what exactly they’ve created.

Why Wonderbook?

JZ: Why ask why? Drink Wonder dry! I think that for myself, I can’t really speak for Jeff’s reason for creating Wonderbook, but I feel it fills an untouched niche in the writing and creation world – the idea that a book can be a learning tool, a visual guide, evolving online resource and objet d’art all at once. It also work works on many levels, which is nice: it’s a fantastic read, a brilliant resource and damn fine looking book on a table. It’s the bumblebee of the writing world – it flies because nobody told it it can’t.

JV: A “sense of wonder” is sometimes denigrated as escapist, but a true sense of wonder earns that description with an edge, in my opinion—it’s grounded in something real or useful or important. There are also the Wunderkammer, or cabinets of curiosities, which in their best examples are expressions of curiosity and passion about our world. Wonderbook is meant to stimulate the senses, to energize, to celebrate and explore creativity, and, oh yes, teach creative writing. But in the sense of an immersive journey.

Does that reflect your idea of how to teach writing, Jeff? Can you say more about this idea of immersion as it relates to teaching?

JV: it’s not always the case that you have the time to pay deep attention to every single writing student you might encounter during a workshop or masterclass, but immersion does mean in reading their manuscripts to try to inhabit the work from the viewpoint of the creator as much as possible, to be sympathetic to whatever the writer is trying to do, not resistant to it. Only by completely inhabiting the manuscript can you then have a good idea of what kind of critique will be most helpful. If you cannot do this, you should admit as much to the student, and frame it in the context of a failure on your part, not theirs. And, in your other interactions with the person, including the workshop itself and one-on-one meetings to talk about their writing, you also gain some idea of the best way to say what you have to say. Again, in an ideal environment. Usually, things are a little too crowded or rushed to meet the ideal, but in trying to do so, and in engaging in a “no bullshit” approach in the workshop as a whole, you can attempt to be of the best use to the student. By “no bullshit” I mean no received ideas about careers that are 20 years out of date, even if this means you need to aggressively analyze your own tendencies to say things you haven’t fact-checked. To in talking about the art of writing to avoid imposing, for example, your top three rules about a particular topic, but instead presenting a range of options, and pointing out which tend to work less well. It’s so important to impress upon writing students that there is no magic bullet—that there is in fact an incredibly self-affirming and fun journey ahead of them of testing out any number of approaches and ideas to find what works best for them.

In some ways Wonderbook seems more like a web or constellation than a discrete object–there’s the text, there’s the art, and there’s the website, which has all kinds of extras and exercises and, from what I understand, is still growing! When I open the book, it seems to want to keep growing, too–color bursts out and lines spread in every direction. What kind of beast have you guys created here? How would you characterize it?

JZ: It started just like that, though Jeff always referred to it as an ‘evolving, living book’ — one that has evolved and mutated and changed, over and over throughout its creation. It was quite complex just on my side handling the initial layout and art, and if you ever see the diagrams that Jeff would send me there were hundreds of bursts of inspiration at random moments. His synapses were firing full bore for a few years there — living stories, evolving hydra, etc. A good book grows with people, and Wonderbook should provide years of growth and development. Of course, some of his notes were on leaves, so he might have just been frolicking in a fit of inspiration from nature.

I like to think that the book’s totem spirit, if you will, is the cover beast – the massive leviathan Lefmatzlaxian, with a city on her back ever growing, reaching into the sky to her sister city above. People really connect with her — she’s very friendly and welcoming.

JV: I wanted a layered book, one that you can go back to again and again and see in a different light. So, in a sense, you choose a path through the book via the images or the main text, or, perhaps a combination of image and the incidental text, or through the sidebar articles. The book is integrated in that you can read it end-to-end, but you can definitely choose your own adventure, too. Given how used to the visual we are in our daily lives through the internet, this layering seemed like it would appeal without being overwhelming.

This is a book for writers that works through pictures, maps, and graphs. Can you say something about the relationship between writing and visuality? What can an image do for a word artist?

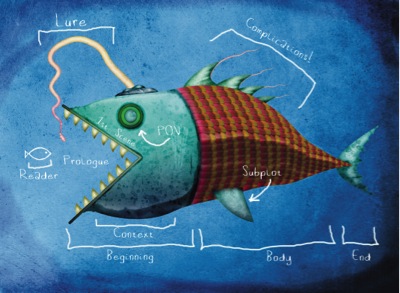

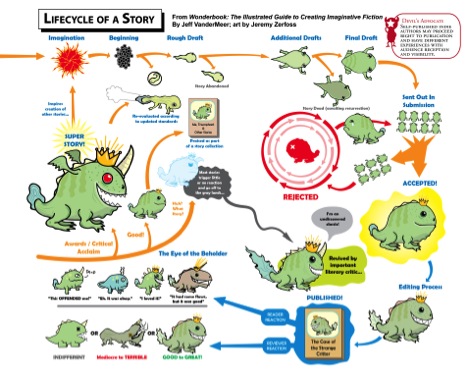

JV: A lot of writers think in images and visualize their scenes and characters, so although all of this is conveyed through words, it’s building pictures in the reader’s mind. So to convey some concepts through illustrations, charts, complex diagrams—this seemed useful. Especially since this meant creating a relationship between concept and image that is the creation of metaphor or analogy—an essential part of fiction writing.

JZ: I’m not a writer, much, but I do feel like the best inspiration for my random writings and artwork come from driving and walking, seeing mountains, old buildings, weird structures, people on random walks, just stuff. My mind always wants to fill the empty places with purpose – you can pull inspiration from an old piece of tile at times, there’s always art or stories waiting underneath the skin of reality, gestating. All you have to do is peek. Much of my art is based on dreams and the desert landscape.

I love what you say about empty spaces, Jeremy. Is there a connection between the desert and dreaming?

JZ: I think every person has an ideal location or setting that enhances their mind, especially subconsciously. For me there is definitely a connection between my dreams and expansive wastelands — I like the blank openness of the desert, the feeling of untapped space and hidden creatures.

Wonderbook seems designed to appeal specifically to writers of speculative fiction. You’ve got all this fabulous weird art, and essays from well-known fantasy and science fiction writers like Ursula K. Le Guin and Neil Gaiman. What about people who don’t write genre fiction? Do you think they’d be interested in Wonderbook? Should they be?

JV: It’s a general writing book that happens to use examples from non-realistic fiction. It uses the vernacular of the fantastic in its images, but is meant to exist at a hierarchical level where any writer can get something out of it. We’ve now got evidence, too, of artists and musicians using it for inspiration. Some of the diagrams, like the Science of Scenes, have helped to inspire a whole CD of music (forthcoming), because the beats and progressions of fiction can, in the attempt to chart them in a pseudo-scientific way, relate more clearly to the beats and progressions in music. I can’t speak to how well it works for any particular creator, but this was the goal: something that will hit the sweet spot of any non-realist out there but also be of use to others as well.

Wonderbook is very playful, both in the tone of the language and in the images–really a delight to explore, which is probably why my kids stole my copy as soon as it arrived. Since it’s sort of a teaching text, I’m wondering if you could say something about the pedagogical value of play. Or maybe just the value of play in general, for artists.

JZ: Playing around with stuff is a great way to explore new ideas and techniques – you have to just drop pretense and screw around at times to get over hurdles as well. Jeff included a lot of fun ideas in the book that are just there to get the mind thinking and I tried to get the imagery as well to incorporate that feeling of fun. Like, don’t be so darn serious, have fun with this. Then come back and let’s kick butt. A few of the images that Jeff loved were born out of random doodles I did on my own, he’d just see them online and email me up and it’d go in the book for no more reason than it fit the spirit and was fun. If you follow Jeff online he’s always posting these random quests for people, “Go to the first person you see and describe them the attributes of a hermit crab and then hi-five them!” or similar things, “Wear something blue, swear it is red when asking for compliments!”, etc.

JV: Play is exercising the imagination, and often a form of storytelling. In that sense, we’re all fiction writers. Encouraging creative play is so important in loosening up the subconscious and giving yourself permission to write, I think. It’s also restorative—like physical exercise it gives back so much to the person who engages in it. While it may seem like a no-brainer to say this, I don’t always think here in the U.S. that the culture gives us permission to engage in creative play just for its own sake.

I love bad advice. Can you give me some rules that express what Wonderbook is NOT about? What are some of the worst pieces of advice you’ve been given as artists?

JZ: Always do what people tell you is right. Never go your own way. Never follow the path untrod. Everyone is right except you. Always obey the rules. The best art is based on people before you, your style will suck if it isn’t just like everyone else’s, that’s why they’re famous and you’re not. Feed the bears.

JV: Wonderbook is not about imposing my view of writing on other writers, which is something you see a fair amount of because it’s, well, easy. It’s easy to just say, “this is what worked for me and thus it will work for you.” What I hope Wonderbook says instead is “there are many ways, and here are some examples of those ways,” and gives space to the writer reading it to bring their own thoughts and opinions into the process.

The worst advice I’ve ever gotten has always had to do with someone not seeing me for the writer I am but for the writer they wanted me to be.

Finally, since we talked about play—a game! I’m going to give each of you three lines from the wonderful guest essays in Wonderbook, and you respond to them as you like. Go!

For Jeff:

“Writer’s block can be as much a matter of perception as reality.” ~ Matthew Cheney (I love his essay!)

JV: I love this essay too. I asked Matt to write it because I don’t have writer’s block–simply because I have so many projects started that I haven’t finished that if I get blocked on one thing, I move to the next one. But I find the constant emphasis on daily word count can make someone who hasn’t written for a month feel blocked even though perhaps all they needed to do is think about what they were writing for a while. I know writers who might think about a novel for a year before ever typing a word. Are they blocked? No. Writing is not about efficiency. It’s not about being part of a machine or being your own factory with stockholders who are clamoring to see a profit from your endeavors, an end product. Writing is messy and inefficient and there’s nothing wrong with that. I am also always struck by those cases of writer’s block that occur because the writer has been denied the time or the space to write—or even the language, like Mercè Rodoreda, forbidden to write in Catalan for so long. Nothing to a pure writer is more painful than being induced into writer’s block. Or even just because life gets in the way.

“As a fiction writer, I don’t speak message. I speak story.” ~ Ursula K. Le Guin

JV: On the slush pile all the time, we see stories from well-meaning writers who think that simple reversals of “normative” situations constitute political statements, who think that imposing their message from on high will somehow get the job done. But politics lives at the sentence and paragraph level, and it comes out through the details of the lives of the characters and their particular situations. So in part this is what Le Guin is saying, and in part that theme is often subtext. Even these three novels I just finished—Annihilation, Authority, Acceptance. Well, they are indeed each about the word that forms their title, but it is all sublimated in situation and character—story.

“I want my stories to contain some things I have no words for, things I cannot say.” ~ Karen Joy Fowler

JV: In part I would interpret that to mean “I write characters that are not me,” but also that things come out in the writing that you didn’t expect, and things come up from your subconscious and into descriptions, situation, and dialogue that you realize form a hidden part of the ideas and issues you’ve been thinking about or reading about. At perhaps the most numinous level, I do believe in an element of the spiritual in fiction, in the sense that some of the best fiction is a reaching beyond, a reaching for some understanding of what cannot be understood. But we must make the attempt.

For Jeremy:

“Sometimes a book will stimulate a series of VIBRANT DREAMS.” ~ Rikki Ducornet

JZ: This is very true — the subconscious will pick up the most innocuous things you read or see or experience and churn it into a frothy mess you’ll wade through some night, maybe years later. Sometimes the connection is hard to see, and I’ve had books that spark a series of vivid daydreams even. I had to stop reading and just go do something else — too much input, too much crazy thoughts.

“Images unseeable from the vantage point of so-called ‘real life’ may be more evocative of the real than the real itself.” ~ Karen Lord

JZ: I have a sneaky feeling this is why books about animals make people cry so much — how many people took a second look at medical and pharmaceutical practices after reading ‘The Rats of Nimh’? On that note… after ‘Finding Nemo’ was released an awful lot of fish were rescued via toilets — reality vs. perceived reality can really take a punch in the arm if you write brilliantly.

“While we’re on the topic of homogenization, I would like to add: Don’t do it. Leave things lumpy.” ~ Charles Yu

JZ: In any form of expression it’s the rough bits that build connections and character. We like characters that have flaws, connectable issues that we can relate to—drinking problems, divorce, health issues, bad days—realistic scenarios that we, as readers, have either experienced or been affected by. If it’s squeaky clean we can’t connect or empathize nearly as well.

I feel art is the same – the stuff that people relate to the most has rough edges and a created feel with soul, depth and humor. The prettiest sunsets come from pollution.

Jeff VanderMeer‘s most recent release is Annihilation from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which will release the other two volumes of his Southern Reach trilogy (Authority and Acceptance) throughout 2014—along with HarperCollins Canada, The Fourth Estate (U.K.), and publishers in 15 other countries. Paramount Pictures and Scott Rudin Productions have acquired the movie rights. A three-time World Fantasy Award winner and 13-time nominee, VanderMeer has been a finalist for the Nebula, Philip K. Dick, and Shirley Jackson Awards. His nonfiction appears in the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times, among others.

Jeff VanderMeer‘s most recent release is Annihilation from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which will release the other two volumes of his Southern Reach trilogy (Authority and Acceptance) throughout 2014—along with HarperCollins Canada, The Fourth Estate (U.K.), and publishers in 15 other countries. Paramount Pictures and Scott Rudin Productions have acquired the movie rights. A three-time World Fantasy Award winner and 13-time nominee, VanderMeer has been a finalist for the Nebula, Philip K. Dick, and Shirley Jackson Awards. His nonfiction appears in the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times, among others.

Jeremy Zerfoss is an artist working out of Las Vegas, who has worked with various publishers and companies including Cheeky Frawg, Raw Dog Publishing, Symantec and Abrams. He was recently nominated for a Hugo along with Jeff VanderMeer for his work on Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction.

Jeremy Zerfoss is an artist working out of Las Vegas, who has worked with various publishers and companies including Cheeky Frawg, Raw Dog Publishing, Symantec and Abrams. He was recently nominated for a Hugo along with Jeff VanderMeer for his work on Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction.